On a murderously cold March morning, we were standing on a narrow river bridge across the Dehar Khud. Traffic was thin, and people in the occasional passing car were perhaps laughing at the idiots shivering in the rain for no apparent reason. The forty minute wait seemed like hours, before a distant toot brought us into action. We all took our positions for the money shot, as the first train of the day on the Kangra Valley Railway rumbled across the bridge. This was the start of a two day adventure, chasing trains up and down the mountain roads.

Tucked in the northwstern corner of Himachal Pradesh, lies the district of Kangra. The rolling hills of this district lie between the towering Dhauladhar Range of the Himalayas, and the foothills of the Shivalik. Drained by the Beas and many of its tributary rivers and streams, the district was a former princely state. Ruled by the Katoch Dynasty, they bowed to the British Raj in the 19th century, and served as their vassals.

In the early part of the 20th century, electricity came to the state and the Shanan Hydroelectric Power project was conceived to meet the growing power needs. Built over the Uhl river, high in the hills above Barot town; a railway line was also proposed to help in the construction of the project. And there lies the origin of the spectacular Kangra Valley Railway (KVR).

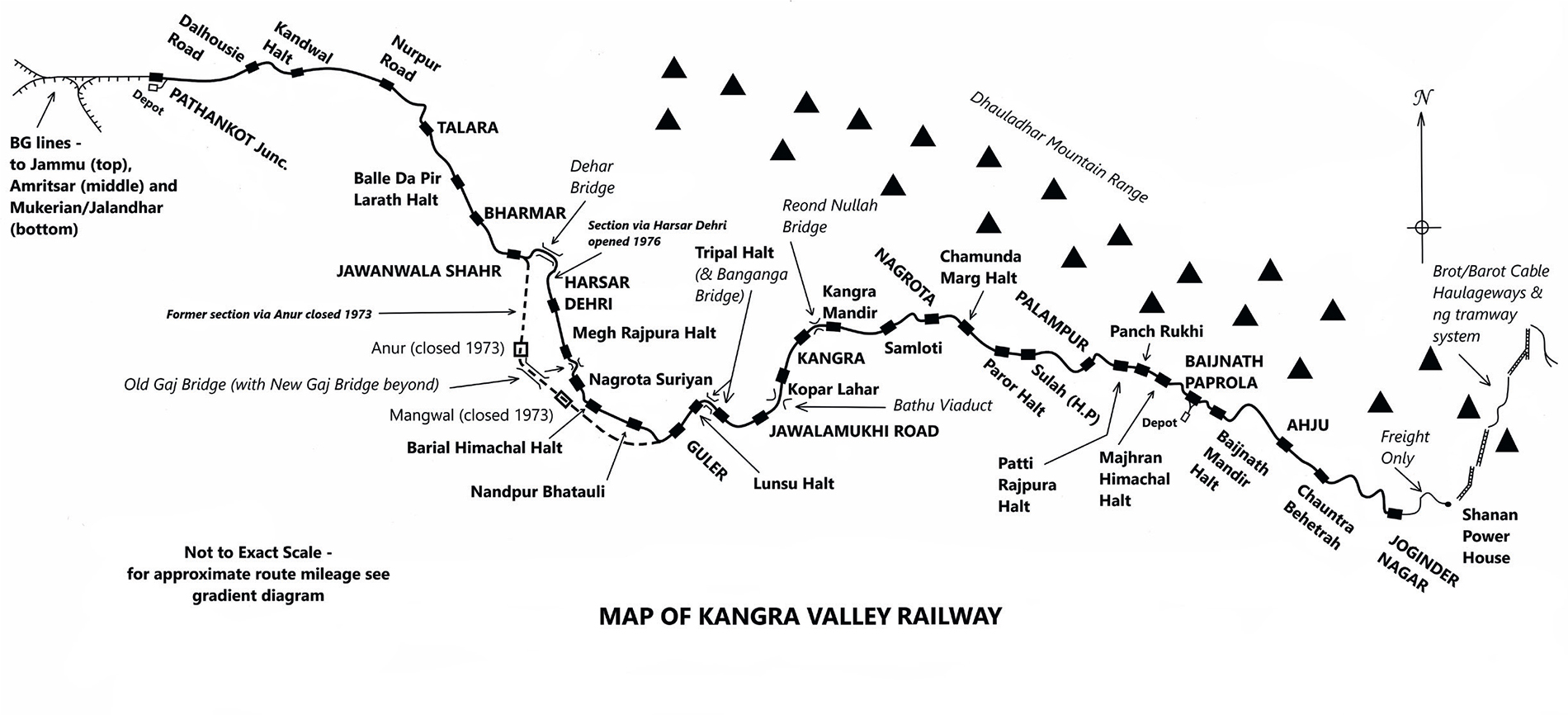

Originating from Pathankot on the Broad Gauge network of Indian Railways, the line crosses the Beas and snakes its way up into the mountains, terminating at the pretty little town of Joginder Nagar, some 163km away. Along the way, it crosses nearly a thousand bridges, five hundred curves, but just two tunnels. The brief to the engineers was clear – keep the line as straight as possible to afford great views of the scenery for passengers. And stick to the brief they did. The much shorter Kalka – Simla Railway (KSR) has nearly a thousand curves and, more than a hundred tunnels for comparison.

Another unusual aspect of the KVR is the presence of three major bridges, one across the Chakki River outside Pathankot (~600m), the Dehar Khud near Jawali (450m), and the spectacular Gaj Khud near Nagrota Suriyan (550m). These were some of the longest bridges on the narrow gauge in India, matched only by the one spanning the Narmada near Jabalpur. Unfortunately, the Chakki River bridge was washed away by heavy flooding in the monsoon of 2022, leading to closure of services on the line. Early in 2023, services were restored partially between Nurpur Road and Baijnath Paprola, and later from Baijnath Paprola to Joginder Nagar. A new bridge is under construction across the Chakki, after significant pressure was piled on the authorities by locals and their political representatives.

This disruption is not the first that the line has seen its nearly hundred year old history. In 1942, the British were in desperate need of iron and steel for their War Effort. As a result, nearly 60 kilometres of track and bridge were dismantled from the section between Nagrota (not to be confused with Nagrota Suriyan) and Joginder Nagar and shipped off to England. Services were only restored in 1954, after Independent India took heed of its people’s needs and rebuilt the line.

Then again in 1973, services on the line were stopped as the section between Jawanwala Shahar and Guler had to be re-aligned due to the construction of the Pong Dam over the River Beas. Four new stations and the current bridge over Gaj Khud were built, and services were restored in 1976. After crossing the Gaj Khud, the line climbs sharply and runs on a new course at the base of the hills lining the eastern banks of the Maharana Pratap Sagar, a gigantic reservoir created by the dam.

The Kangra Valley is famous for its temples, such the Bhagsu Nath Temple, Chamuda Devi Temple, Kangra Devi Temple, Baijnath Temple and many others. The Jwalamukhi Road station serves as the railhead for Jwalamukhi Temple, which was built in the 19th century. Many pilgrims alight here and the market above the station also serves as a rest stop on the highway from Pathankot to Mandi. The station building with its sloping tin roof is typical of these parts. A landmark outside the station is Sharma Punjabi Dhaba, a nondescript eatery made famous when the IPL cricket Teams stopped here for lunch on their way to the stadium in Dharamsala. Today, it is better known as the Dhoni Junction! But forget the cricket lore – the real reason to be here are the amazing paranthas. Warning: leave your calorie counter outside.

The district headquarters at Kangra lie roughly halfway between Pathankot and Joginder Nagar. Situated on a ridge roughly 2,400 ft above sea level, it is a bustling town. The 16th century Kangra Fort dominates the landscape and is the site of the former princely capital. The old parts of the city were damaged badly in the 1905 earthquake, and many relocated to the town’s present location some distance away. For those more interested in the railways, there is the spectacular Reond Khud bridge (Bridge #459). It is unique in its construction due to its three-pinned steel arch stretching 180 ft. This is supported by 40 ft plate girders at either end. The main span of the bridge was constructed by projecting a cantilever portion on either side, and then connected with the central pin. It was fabricated by Braithwaite and Co. in Mumbai, and erected in just six weeks.

Things only get more beautiful as the line climbs towards Baijnath Paprola. A little known aspect of Himachal is that it is India’s third biggest tea growing region after the Western Ghats and North East India. Kangra Tea is famous in its own right, and the tea estates around Palampur are as pretty as they come. Palampur station itself is among the five most beautiful railway stations that I have been to. The Dhauladhar mountains tower over the station, with gold and green trees lining the platform and its charming tin roof.

Legend has it that the town gets its name from three Hindustani words —pani (water), alam (environment) and pur (settlement). Ergo, the ‘town with plenty of rainfall’. Mercifully, the rain had abated on the day we visited the station, and the golden sunrise over the snow capped peaks of the Dhauladhar made the setting beautiful beyond words. And the the arrival of the morning train to Nurpur Road made it picture perfect.

While services ran all the way from Pathankot to Joginder Nagar, they were operating in two parts when we visited. Two pairs were running between Nurpur Road to Baijnath Paprola, and another two pairs between Baijnath and Joginder Nagar. Strangely, the timings of the two pairs were not synced, to allow passengers to connect end to end. Baijnath Paprola station gets its name from the famous Baijnath town which is actually closer to the Baijnath Mandir station. The location around a nearby town called Paprola was more suitable to allow the construction of a fair sized yard and a trip shed for visiting locomotives.

When opened, the trains on the section were powered by steam. ZE and ZF class locomotives were house in a shed (depot) at Pathankot. This was later converted to diesel traction in 1976-77. ZDM-3 class locomotives built by state owned Chittaranjan Loco Works (CLW) were brought for duty. These 700hp locos were later supplemented by the ZDM-4A class, which were largely identical but featured two extra axles for better adhesion. The steep section between Baijnath Paprola and Joginder Nagar is the exclusive domain of the ZDM-4A class. The original ZDM-3 class built between 1971 and 1982 has been phased out. In its place, a modern twin cab ZDM-3 (internal designator ZDM-3D) class is in service, with locos built by the Parel Workshops in Bombay.

The trip shed at Baijnath Paprola was meant for performing inspection and light repairs on the locomotives, while the main shed at Pathankot too care of heavy repairs and overhauls. However, with the connection to Pathankot now severed, the locos were brought over by road to Baijnath and the trip shed is now taking care of all maintenance. 7 locos in all were being kept in running condition at that point. Trains on the Nurpur – Baijnath section were running with 5 coaches, and with 3 coaches between Baijnath and Joginder Nagar.

The most spectacular scenery however, is reserved for the section between Baijnath and Joginder Nagar. Passing through Baijnath town, the line climbs through alpine forests along fast flowing streams. Snow capped peaks keep company as the line winds up to its highest point at Ahju, at an altitude of 4257 ft above sea level. A maintenance train, hauled by a farm tractor converted for railway use can also be seen at Ahju.

Pine forests and terraced farms dot the countryside as the line climbs further up. A lovely horseshoe curve signals the arrival of Joginder Nagar station. The end of the line is rather anti-climactic. Joginder Nagar is a time station, with a platform line and two loops. The loco quickly ran around to the other end, and prepared for the downhill run, scheduled to depart in an hour.

The monsoon of 2023 ravaged Himachal Pradesh, and the Kangra Valley Railway fell victim, along with other roads and rail lines in the state. At the time of writing, services were yet again suspended on this line, with no reopening date in sight. Nevertheless, owing to its importance to the locals, Indian Railways has promised a complete restoration of services till Pathankot. When that’ll happen, is anyone’s guess. We were, however lucky to experience the charm of this section first hand. Leaving you with a few more images to savour.

With special thanks to CPRO office Northern Railway for permission to shoot on the line. My friends AS, RU, BM, VP and Dr. K for braving the weather and the banter. And our driver Abhishek for keeping up with us mad men.

A Wonderful blog!

Great writing and visual treat for the weekend!

Excellent Write up Shanx..Beauty of KVR with Towering Snow capped Dhauladhar and the colourful Locos and Coaches very well described..

A highly artistic and valuable record of one of Indian Railways’ few remaining treasures! One for posterity!

Fantastic set of pix and write-up, Shanx! Very atmospheric. Would love to explore this line someday. Looks like you guys had a lot of fun.