In a tiny spit of Rajasthan – sandwiched between Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, lies the town of Dhoulpur. Once a not very significant princely state, the Dhoulpur Maharajas still managed to build their own railway network. Chiefly to transport the state’s main export – the famous Dhouplur stone. For those who don’t know what that is, think – The Rashtrapati Bhawan, The India Gate and the Parliament House.

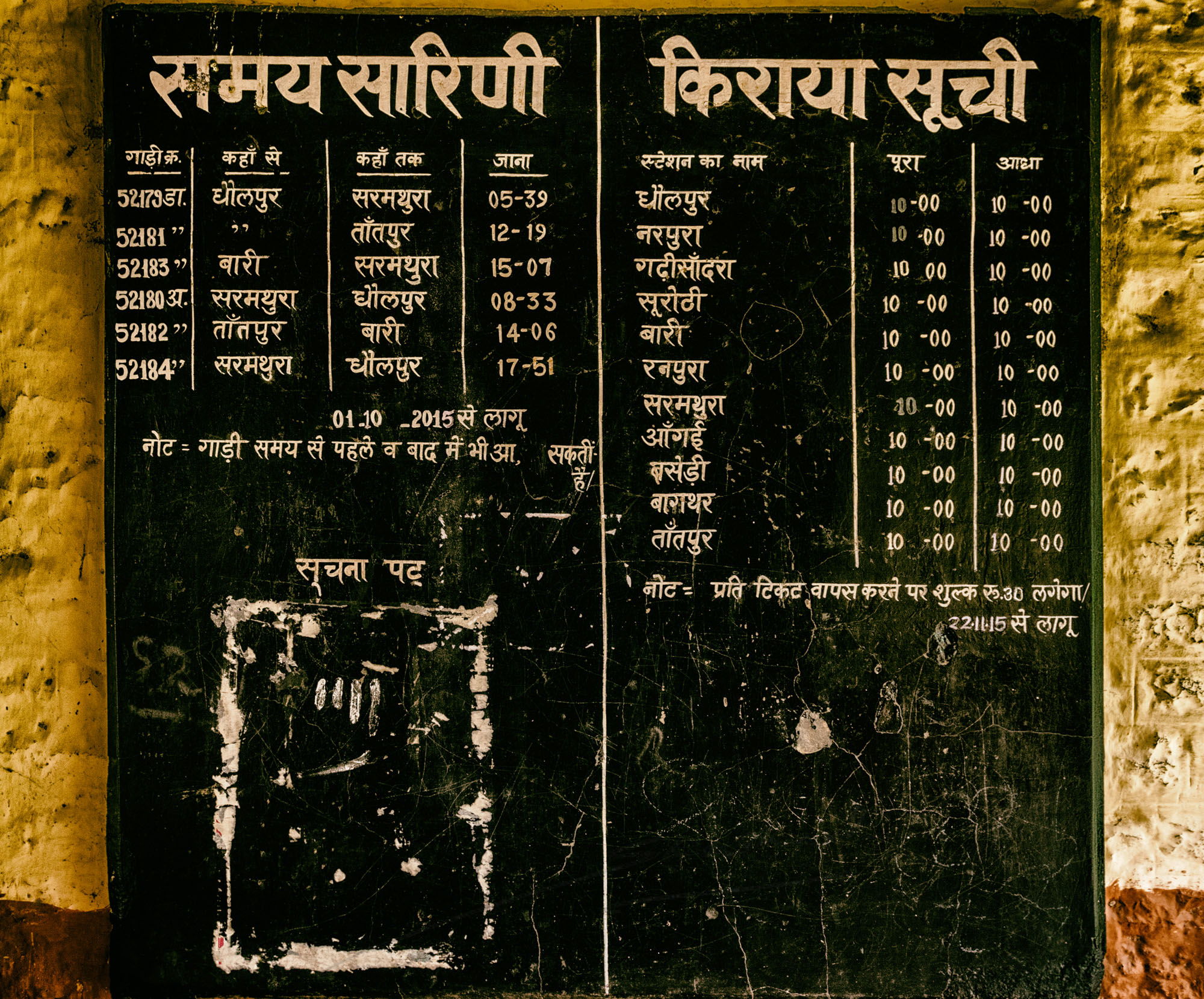

The railway opened in 1908, with the main line between Dhoulpur and Bari, with branches to Tantpur and Sirmuttra radiating from the junction at Mohari. With the passage of time, roads have become the primary mode of transport, owing to better connectivity and faster speeds. But the train still soldiers on, well patronized by locals, who find the flat fare of Rs. 10 very attractive.

The sceptre of gauge conversion looms large on this line. But even in its twilight years, it manages to fulfil its purpose, while delighting the railway enthusiasts who manage to find their way to these parts.

The late morning service to Tantpur departs Dhoulpur station. A family of feral pigs, barely manages to escape being run over.

There is barely any space, neither in the train, nor in the water. Yet – they all look comfortable.

There is barely any space, neither in the train, nor in the water. Yet – they all look comfortable.

Almost every station is as atmospheric as Soorothee. The names still spelt with their Anglicized pronunciations

Passengers wait for the train at Mohari Jn. One of the last few Narrow Gauge junctions left in India.

The idiosyncrasies of the bureaucracy often bare themselves in the furthest corners. The line runs on a maximum fare of Rs. 10 for any station. Yet, if a passenger wishes to return his ticket, a standard charge of Rs. 30 is applicable.

I doubt, if a ticket was ever returned at this window.

A group of ladies take position to grab a seat as the train enters Mohari. Whatever be the setting, the colorful sarees of Rajasthani women always stand out.

The 5 coach train crosses the Parbati river on the outskirts of Mohari. The waters in these parts used to be some of the cleanest. But now plastic and garbage are beginning to choke these pristine streams.

Having arrived at Tantpur (which now falls in Uttar Pradesh), the driver’s assistant prepares to switch ends for the return to trip to Bari. The train will switch back again there, and make the run to Sirmuttra.

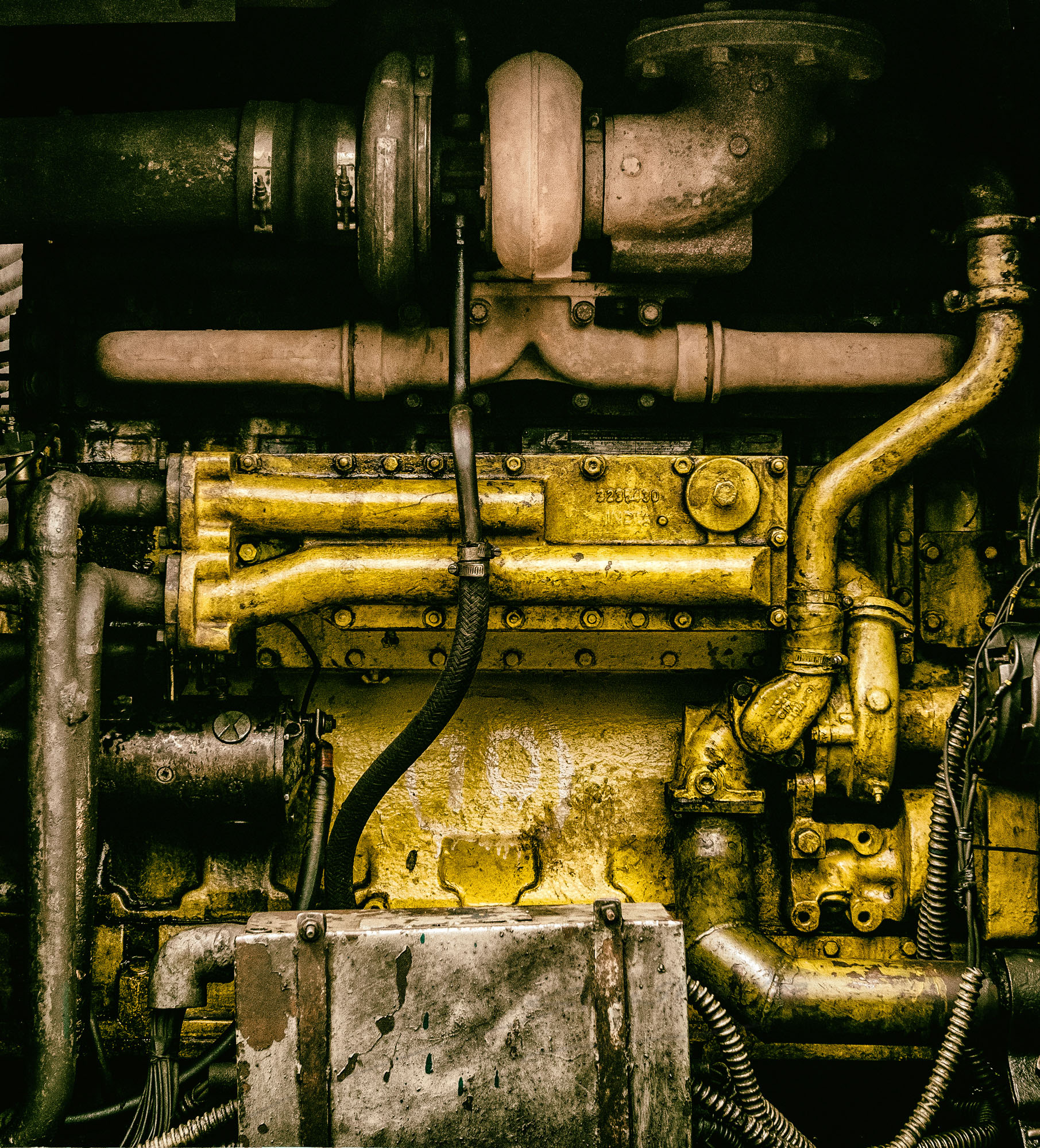

In the days of the maharajas, locomotive sheds often had ornate emblems depicting their names. Not so in the functional world of the modern Indian Railways.

The ageing heart of the beast. The locomotives are usually underpowered and overworked. So they are usually run with the doors open for that extra draught of air for cooling.

The run to Sirmuttra is dotted with stone quarries. The surplus is used to create boundary walls to demarcate the railway property from the private.

The end of the line at Sirmuttra – a nondescript town in a hard to find corner of the map. The filth of its bustling streets has spilt on to the railway station as well.

India is growing too fast to keep up with itself. The tiny railways are struggling more so. It is only a matter of time, before they are overtaken by modernity. The ubiquitous broad gauge – devoid of any character or charm.

Wonderful post. Thanks for sharing this unique part of IR

Excellent. Virtually the last of its breed

Lovely photos and a very engaging article.

Good information

Beautifully written and presented with the pictures.